Presidential Election in Austria and Rise of the Far Right

The Association for the Anthropology of Policy

Cansu Civelek (University of Vienna)

March 2, 2017

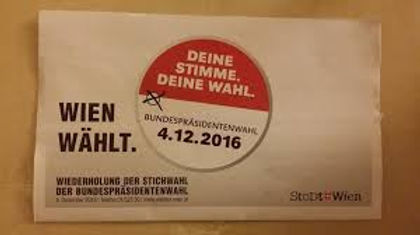

On December 4, 2016, Austrians elected Alexander Van der Bellen, a former member of the GreenParty, as the President of the Republic. Though 53.3% of the votes went to him, almost 47% went to Norbert Hofer, the nominee of the far right from the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ). In Winning aBattle, Not the War, Walter Baier urged readers to consider that a significant number of people voted for Van der Bellen to stop Hofer, whereas most people who voted for Hofer did so not because they wanted to stop his opponent but because they wanted his politics to win.

As parties on the far right are gaining ground around the world, it is becoming important to understand why people, including minorities and workers, are voting for parties on the far right,rather than parties in the center or on the left—parties that have historically represented their interests.

Curiously, pollsters failed to predict the results of recent elections, such as the Leave campaign inGreat Britain or the Trump campaign in the United States. When considering the shock that was felt and discussed by anthropologists at the 116 Annual Meeting of American AnthropologyAssociation shortly after Trump’s victory, ethnographic research is very timely. A number of discussions and an invited session, “Anthropologists React on What Just Happened,” sought to understand the reasons of Trump’s victory and discussed what we could do in the future. Panelist Janine Wedel addressed not only the critical role of anthropology in times such as these but also moved beyond the American political agenda and pointed out the alarming threats of the far right across Europe, including Austria.

A polling card

A case study of the presidential elections in Austria will help us move beyond polls to more deeply analyze social transformations and changing voting patterns. With the help of a colleague, Hayri Can, in the field, I researched the conservative Turkish community, a sidelined group, who came toAustria as guest workers, whose political orientation is pro Erdogan in Turkey. How can we explain the emerging support for the FPÖ, when the same party has scapegoated them? I visited Vienna’s neighborhoods where the Turkish community has a large presence: District 10, also known as “Little Istanbul,” District 16, District 20, as well as mosques, bazaars, and coffee houses, where I talked to approximately a hundred people across three generations.

Almost all informants expressed that their interests are not represented by any of the political parties in Austria. Their expressions of “being a second-class citizen” and “loneliness” were most common. One retired man said: “I and all my friends voted for the Social Democrats for years. What changed for us? Nothing. We are still ‘the other.’” Another said: “There is no unifying party in Austria.Every party is like a company, getting their own business done. But rents are rising, people are in depression, and nobody cares about the real struggles of people.” They repeatedly complained about the “two-faced politics of the SPÖ and the Greens.”

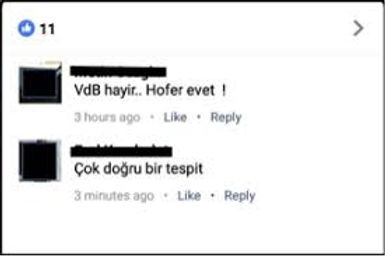

Two Turkish Facebook comments: “No Van der Bellen, Yes Hofer!” and “Definitely right point.” Cansu Civelek

Almost half said they would not vote, some said they would cross out the two candidates’ names and write down “Erdogan: Yes” to “demonstrate their unrepresented voices,” and a few said they would vote for Van der Bellen since he was the “lesser of two evils,” as a group of women said.

Yet, some people preferred to vote for Hofer, FPÖ’s nominee. A young waiter said: “Both Greens and SPÖ go to visit the Turkish Embassy. They would run there if they offered free champagne. But I’m not living in the embassy. I’m living here.” The loss of trust in the SPÖ and Greens over the years made this group seek out political alternatives.

Compared to Van der Bellen, people and Hofer to be a strong leader, who “at least has a real and strong political agenda and leadership unlike the passive Old Wolf [Van der Bellen],” according to another second-generation man. A first-generation man said: “Hofer has leadership qualities. Vander Bellen couldn’t even convince people that they didn’t make mistakes counting the last votes.Even an ordinary worker holds his head higher than him.” During a group conversation in a coffeeshop people claimed: “FPÖ is 80% right in what they propose. Hofer has targets and a political agenda. He doesn’t want vagabonds. We don’t want them either. Anyone who loves his country serves his country. I’ve served this country a lot and have no fears. Vagabonds should fear themselves.” Another man shouted from the next table: “I’ll also vote for the one kicking the vagabonds out.” Moreover, Hofer’s religious references seem to be paying off. People and him to be a believer who fears God, which makes him a more honest candidate. A business owner said, “Hofer takes God beside him, like Erdogan.”

It has been known and discussed for decades that the Turkish community in Europe voted for leftist and social democratic parties regardless of their support for conservative parties in Turkey. Social democratic parties’ policies on the basis of human rights and the rights of migrants and refugees, converted even more conservative Turks to left-wing parties as they understood that beginning anew life in Europe would depend on the advancement of social and welfare policies. While they did not vote for left-wing parties based on class consciousness, supporting the left was indispensable and pragmatic, as they mainly made a living as laborers in industry.

Yet today, Turkish migrants started supporting right-wing parties and even far right parties. Despite ongoing difficulties, second- and third-generation Turks have settled in and laid claim to Austria and its political agenda. For instance, new waves of refugees and migrants have led to different reactions among the Turkish community. As the social policies have moved more towards refugees, former migrants have borne the cost of supporting newer migrants financially and socially. Some of my informants complained that their taxes are supporting vagabonds. It appears that the easier answer for some citizens with migration backgrounds has been to disregard their own past struggles, and submit to strong leaders and their policies of socioeconomic “stabilization and strength.”

Meanwhile, leftist and social democratic parties worldwide failed to establish bottom-up politics and projects, partake in people’s everyday realities to represent their struggles, but instead organized politics through the monopoly of the “cream of society” and became elite parties—the Turkish community in Austria calls them “champagne parties.” This provided a ground for right-wing and even far right parties to be supported even by working classes, minorities, and migrants. When people feel established, especially economically, and when the left no longer represents their interests, some people revert to their conservative ideologies. One of Hofer’s supporter said: “One returns back to one’s origins,” meaning that supporting left-wing parties is passé. By taking advantage of the left’s failures, the far right has risen worldwide with “stability” solutions against what they call “instability” problems, which are, in fact, products of capitalism and byproducts of deregulation, privatization, financialization, job insecurity, and other social insecurities.

Finally, after we presented our research in a Turkish newspaper, a parliament member from theGreen Party of Austria commented that our findings were simplistic. She added that she worked with the Turkish community for years and knows them very well. Her reaction of “knowing everything better than anybody or any research suggests” summarizes the points I made about the left’s distance from people’s realities and their transformations.

I agree with Walter Baier that Austria “won a battle, not the war” against the far right and that Vander Bellen’s victory is only a breathing space rather than a solution to the crisis of Austrian democracy. To continue to fight against far right and populist politics in Austria, in Europe, and in the world, researchers will not only need to engage in careful and deeper research but also reach beyond academia to the wider society to contribute to breaking the right-wing’s increasing legacy and hegemony, and to develop alternative languages and projects.

Cansu Civelek (civelekcansu@gmail.com) is a PhD candidate and Uni:DOCs Fellow in theDepartment of Social and Cultural Anthropology, University of Vienna.

A link to the article on the Anthropology News website can be found here.